Fiction & Drama

New Northbank fiction in 2024

04/01/2024

It has been said that literary fiction is character-driven while genre fiction relies on plot to engage the reader. But, if plot is important to genre fiction, it is far more so for the sub-genre Police Procedurals, crime novels told wholly from the point-of-view of the investigating officer.

The rule of thumb is that nothing must be shown to the reader which is not also available to the detective. There are exceptions, of course. Twin narratives give an insight into the minds of both criminal and detective. In such cases, the criminal’s narrative may be an internal monologue, their identity and whereabouts being concealed from both reader and detective until The Big Reveal.

When I began writing crime fiction, my first attempt was something of a mongrel – a bit of this, a bit of that. On showing it to an editor friend, I was advised that the strongest scenes were written from the detective’s point of view and that I should focus on following the detective in future novels.

The mongrel remains buried in the depths of a hard disc, never to see the light of day. But I learned a great deal from the experience and began planning the next novel. With a ready-made set of police characters, it was tempting to plough straight in. But, by now, I knew the importance of careful plotting in crime fiction.

Yet here, crime novelists can be divided into two distinct camps – those who plot, and those who write to find out what happens. At a Q&A session many years ago, I asked the novelist Ian Rankin how he set about concealing the truth from his readers. I was surprised when he said he sometimes doesn’t know the identity of the murderer until near the end of a novel. I will admit, my characters can sometimes surprise me by doing the unexpected but, with deadlines to meet, I find proper planning lets me sleep more easily at night!

The first task is to find a crime which will keep readers engaged. A simple, unexplained murder may not have the desired complexity so the search for back-stories, motives and sub-plots begins.

In common with many writers, I have a collection of notebooks – each small enough to fit into a coat pocket or handbag and I am rarely to be found without one. I skim through TV programmes such as the BBC’s Rip Off Britain and Ill-Gotten Gains, for examples of unusual crimes. My local newspaper is another rich source of ideas, from the bizarre (a man caught riding a space hopper along a Dundee dual carriageway on New Year’s Day) to the chilling (the infamous Robert and Sonny Mone, father and son killers with no conscience). Even a chance remark by a friend can be noted down for future plotting. As well as the notebooks, I use the Notes app on my iPhone. Glancing quickly at the app today, I can see the first few lines read:

Multi-storey car parks

Freeze bank accounts

Street food vendors

It may be that none of the above makes it into a book but sometimes it can be the smallest detail which sparks a train of thought.

I dislike being rushed so I begin the process well ahead of a deadline. I start by opening a Word document and typing up the jottings from my phone and notebooks, grouping them under headings such as MAJOR CRIMES, MINOR CRIMES, SETTING and so on. As well as throwing up potential plot ideas, this transports me back into the lives of my characters, a useful technique for ensuring consistency across a series.

The next task is to decide on a broad theme to weave through the novel. Usually this will relate to the central crime to be investigated. The theme need not be clear to the reader at the outset. Murders committed by a serial killer could be the central crime but the reason for these murders might be discovered later in the novel and this is where the overarching theme comes in.

In common with real police investigations, there will be other, minor storylines (or sub-plots) running alongside the central crime. As a reader, I find novels more satisfying when the theme pervades all these threads, even if the link is tenuous in some cases.

Once the central crime and theme are determined, I turn to PowerPoint and this is where the planning begins in earnest. I work through the plot, creating one slide per scene. At the head of each slide is the date and time in a large font with the scene described briefly below. I find it easier to begin by creating slides for the beginning and end of the novel; and, as I develop the plot, the middle ground is gradually filled in.

In crime fiction it is essential that events happen as the detective discovers them so it’s worth taking time to read carefully through the completed slides. There are always continuity errors – events in the wrong place, repetition or even important actions missing. A bit of care taken at this stage can avoid the misery of untangling a plot, weeks or even months down the line. I use Slide Sorter view to drag the slides around, deleting and inserting new ones until the plot runs in a logical order. I also add slides which contain information known to me but not to be divulged to the reader at that point. These are coloured yellow to remind me not to include the information they contain. Once I am satisfied the slides are correctly ordered, I leave them again for a few days before returning for one last check.

The final planning stage is to export the text from the slides into a new Word document, giving me a ready-made novel plan. The groundwork is done now and the job of writing the novel can begin.

In theory, working to this kind of plan should be straightforward. But, as I look at the seventy-two-slide plan before me, I am reminded that writing crime fiction is rarely straightforward. And that’s the very reason I love it.

–

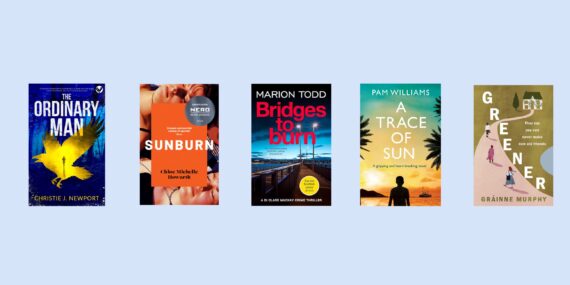

Marion Todd recently signed a three book deal with Canelo. Her first book will be published in October 2019 with the following two novels due out in 2020.