Children’s & Young Adult

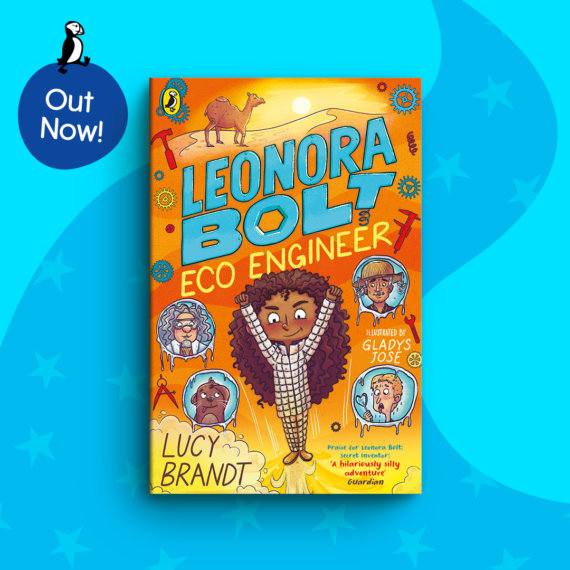

Lucy Brandt’s Leonora Bolt: Eco Engineer published today by Puffin

20/04/2023

20/04/2018

The main difference between writing for children and writing for adults is the attention span. Children don’t want to wait around for the story to get going. They want to jump on a moving train.

Read a few paragraphs to children and you’ll soon know whether what you’ve written will work. If it isn’t working, they’ll tell you so. Or worse, they’ll just start doing something else instead of listening, like picking their nose or asking you random, un-related questions like: who would win in a fight, Spiderman before he’s turned into Spiderman or Clark Kent before he’s turned into Superman? If you find yourself trying to think of an answer, it probably means the story you’ve written, or at least the part you were just reading, needs work.

The other point with writing for children, is that it’s very easy to overestimate their knowledge. Simple words can hide complex concepts. A word like “betray” has a hundred whys built into it. To have betrayal, you have to have trust, to betray the trust, you have to have a good reason, or a maybe a bad reason.

The language and plot are simpler in children’s books too, although nowadays a lot of adult books also tell their story in short sentences and are careful to avoid big words. It’s the fashion. It’s also the fastest way to turn what’s happening on the page into story, making the distance between your reader and the thing that really matters as short as possible.

It wasn’t always this way. Read Beatrix Potter to your children (or even to yourself) and you’ll be reaching for the dictionary, puzzling how exactly you explain Uncle Bouncer the Badger’s “lamentable want of discretion”, or why Benjamin Bunny had to dig “quite a deep hole” to find dog darnel. Dog darnel is a kind of grass. I don’t know why Benjamin Bunny had to dig “quite a deep hole” to find it. Not a very deep hole, not a shallow hole. Quite a deep hole. Grass grows above ground. Was he looking for the roots? Potter doesn’t tell us. But that’s part of the fun of Beatrix Potter, you experience English as if it was a foreign language. And by the time you’ve explained what the words mean, the kids are asleep.

Children’s books are shorter but that doesn’t mean they’re easier to write, or that you can finish them more quickly. I find it takes longer to write less.

You whittle away, wondering whether the joke about bagpipes being the only musical instrument scientifically proven to cause indigestion should really go on for a side and a half, or whether the chapter in which a minor character explains his thesis on the history of the marshmallow should be cut.

In the end though, they have one thing in common. They are both about loss, about the missing bits, the suggestion there’s more coming to answer the questions the last few pages set off in your head. Whether you’re writing for adults or children you’re doing the same thing, you’re tying together a narrative net. It needs holes so the reader can pull it through the water and fish out the meaning. Carefully controlled, purposefully-placed suggestions. A gold coin, a wooden leg, a treasure map in a bottle.

–